I’ve been rethinking all of my lessons this year. My hope has been to get my students to reason more. To think independently. To not be sponges. I’d like to think it’s been working. Here’s a recent lesson on summation notation that showcases this shift.

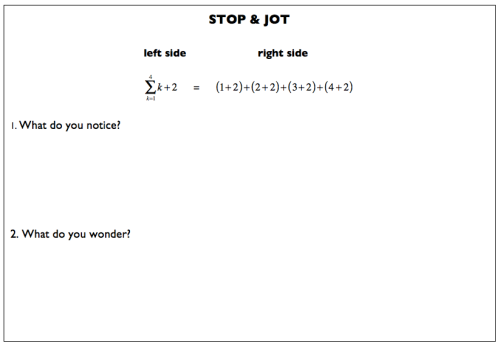

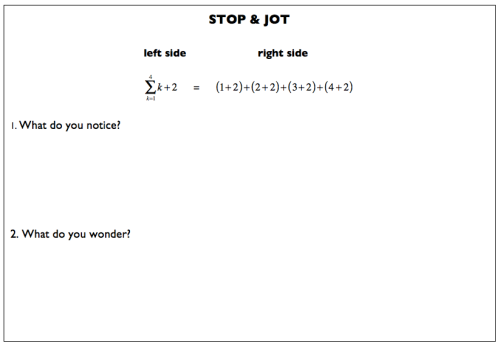

To open things up, I gave them this.

Super accessible and relevant to summation notation. In the past, I would have chosen a bell ringer that was closely connected to a prior lesson (i.e. review) than the current one. I wanted to provide remediation. I’ve learned this year that a relevant bell ringer is pivotal to any lesson.

Here’s what came next.

Again, very accessible. Last year Jennifer Preissel mentioned the “Stop & Jot” idea as a simple way of getting kids to write and reflect more during a lesson. Here, I gave them five minutes to express, on their own, what they wondered and noticed about the expression. After, they shared with their groups and we discussed as a class. By including “left side” and “right side,” I wanted to focus student responses. There were comments like “the +2 happens in every parenthesis” and “the number next to the +2 is going up by one.” Their observations led us to the brink of directly relating sigma notation to its expanded sum. In the past, I would jump right into defining sigma, the upper and lower limits, argument, etc. There would have been no exploring or thinking on their own.

Next, I ask them to move on to another example with the hope of finding a relationship.

It worked like magic. They see the same pattern from the Stop & Jot and they start to generalize. They have no idea what the “E thing” is, but it’s beginning to settle in how the left and right sides relate to one another. They discuss all of this in their groups. I float around. Observing. Listening. In the past, I would show them how to find this sum and answer their questions. Again, no self-exploration and making meaning of what they see.

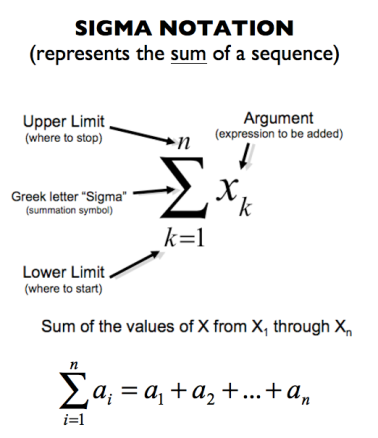

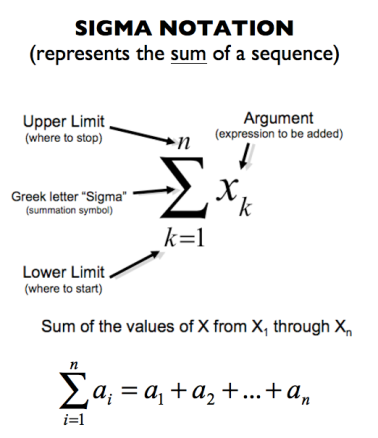

Now they are to dissect and interpret.

This lacks clarity. Some students knew to write their interpretation next to the arrows, but many did not. As a checkpoint, we came back together and discussed.

Next: remove the right side.

Things are flowing now. The scaffolds are working. They know the relationship and successfully express the sum. In the past: The students would probably be completing this problem, but instead of using their own insight to drive the work, they’d be following what I said was the correct procedure.

Finish it off.

We come back together one more time to debrief and to address any questions the groups haven’t already. To bring things full circle, I mention the task from the bell ringer. “Ohhh!”

Lastly, on the next page, the proper names are reveled.

We then have just enough time for an exit slip.

This lesson is heavy on notation and I didn’t want to bog them down with symbols. The goal was to find meaning first, then discuss representation. It succeeded. What I miss out on is working in reverse. Namely, using sigma notation to represent a given sum.

What I love most about this lesson has little to do with summation notation. It’s much bigger. It stems from the approach. Bottom up. Using their own insights to help them find meaning. Doing less and allowing them to put the pieces of the puzzle together. This lesson is a microcosm of how I try to teach nowadays, which is much different than in the past. It symbolizes my growth as a teacher, as a learner.

Here is the handout.

bp